Beyond the Instruction Stream

Interview with Ilan Tayari, VP of Architecture at NextSilicon

One of the things I love about computer architecture is when people do things that are innovative. We’ve been dealing with the same sort of computer architecture for the last 50 years. GPUs did something different, and then we also have ASICs, DSPs, and architecture like VLIW, very-long-instruction-word, all trying to extract performance in different ways but with a variety of different limitations.

Some of these limitations are more educational than practical - but some of them lend themselves to performance enhancers like power efficiency or memory bandwidth. Beyond that, while we have ISAs like x86, Arm, and RISC-V, the industry is now full of these - but they all roughly delineate down into very specific lanes. That is why we have a proliferation of software stacks and such that go down each of these routes.

So when a company turns around to me and says, “We’re doing something different and it’s going to accelerate a bunch of things,” I often turn around and say, “Well, show me the proof. What data are you getting? What exactly are you accelerating?”

Insert NextSilicon, a company taking a very different approach. I interviewed the CEO on the run up to their latest Maverick 2 processor launch - but one thing I learned from that launch, even as a semi-insider, is that there are really smart people inside. I like speaking to smart people because they sometimes have funny stories, but they can actually tell us what’s going on underneath - and what they’re thinking at any given time.

So enter Ilan Tayari, VP of Architecture from NextSilicon. I sat down with him at Supercomputing 25 to dig deeper into their new architecture and why they believe it solves the problems of modern high-performance computing, both HPC and AI.

The following is a cleaned up transcript of the video above.

Ian Cutress: Take me back to where you were, seven years ago as a co-founder, and thinking about doing something different.

Ilan Tayari: My background is mostly software. I’m a software guy, but part of my sins is that I used to work for Mellanox. In Mellanox, I had to go deep into the hardware features and understand the hardware architecture. One of the things that I learned about hardware is that pipelining things is part of making it go fast. That is when the idea occurred that you can take an application and pipeline it.

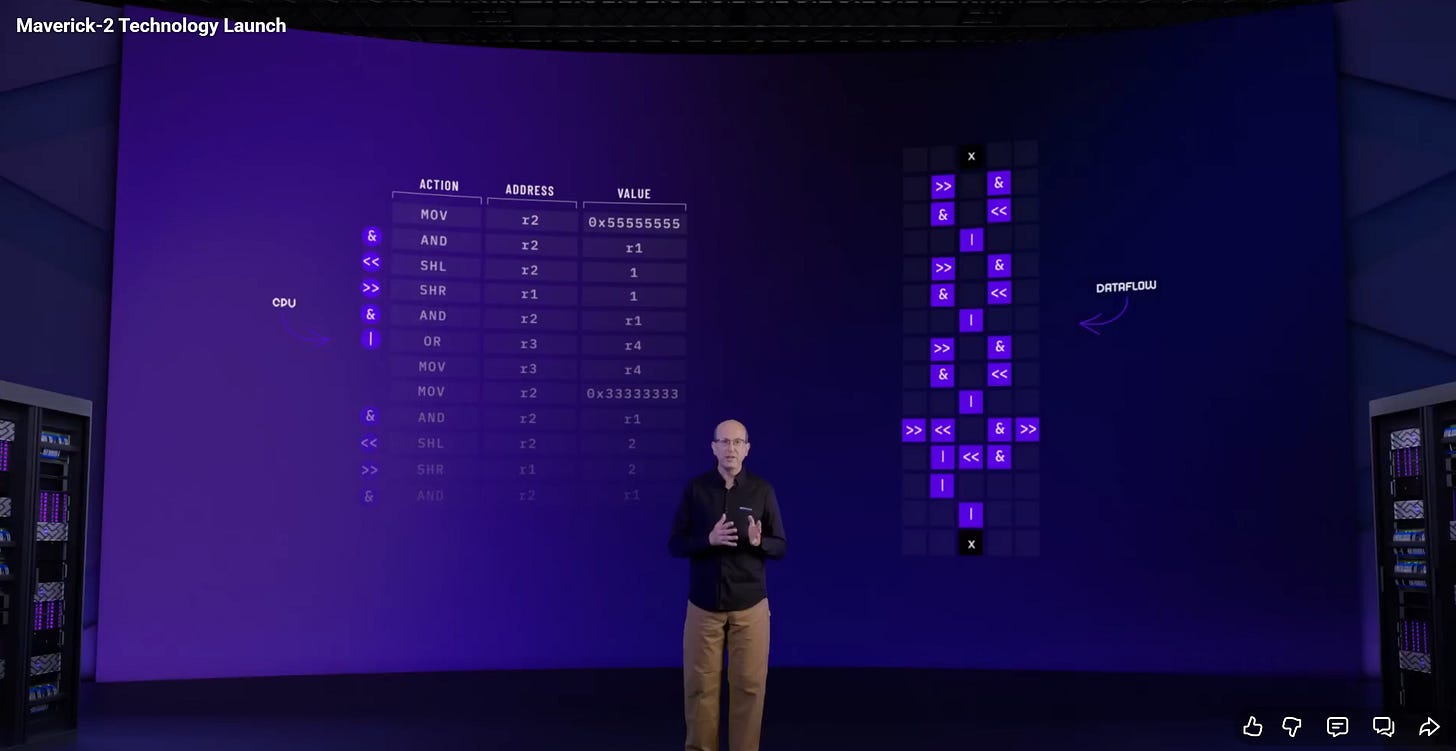

CPUs and GPUs are based on the Von Neumann architecture that you mentioned, which is eight decades old and is not new in any way. All these CPUs and GPUs are doing the same thing. When you run your software on these architectures, you are taking C/C++ code and compiling it. Compilers - and you can see this in LLVM practically - they use an intermediate representation which is a graph. This graph represents dependencies between the operations. Then, you take that and serialize it into an instruction stream. The silicon in the computer core reconstructs the graph. It has to reconstruct the dependencies and see what depends on other things and what does not in order to reorder them.

Ian: It does that line item by line item?

Ilan: Yes, but it is more than that. A processor runs ahead of your program, fetches more instructions, and figures out what depends on what. It can issue multiple memory outstanding operations and multiple ALU operations at the same time, not in the order that you wrote the instructions.

Ian: But that means it is faster!

Ilan: Yes, exactly. It is hiding the sensitivity to the latency of the core. Now, what if you could do away with all that? Simply take the graph, the intermediate representation, and make hardware that executes that. Then you get something that is pipelined without the overhead of reconstructing the graphs. Why do the lowering and then the lifting if you can just pass through that and bypass the transformation? Then you get something that is more efficient. It is at least as performant, if not more, because it doesn’t get things wrong in the sense of ordering, and it is much more efficient because it doesn’t have to deal with instructions.

Ian: I’m going to play devil’s advocate here and say that when I write and run my code, I don’t necessarily care or see what is happening down the chain, but I know there’s an underlying instruction set architecture (ISA). When you are saying you are running a graph, surely you are also converting that graph into some lower ISA for it to run on the chip?

Ilan: When you say ISA, it is a term that has a lot of connotations. People think about an instruction set encoded like x86, RISC-V, or Arm, where you have some kind of encoding for each type of instruction and they come in a stream. But when you compile, the intermediate representation, it’s made out of operations that are laid out logically in a graph, and you don’t have to serialize that into a stream of instructions.

I’m talking about hardware that can run the graph directly by configuring different elements. Let’s say you have an element that does addition, one that does shifting, and memory access obviously. You just lay them out with the connections. Once they are laid out, you don’t need to stream instructions back and forth. There is no instruction stream. There is no instruction fetch. There is no reordering of instructions.

Ian: I want to think about it mentally in the sense that, yes, when you compile and get down to the assembly level instructions, it is just a linear vector of instructions that get loaded one by one. Yes, you may have dependencies and they get figured out. What you are saying is more from the graph; you can almost turn that into a 2D representation of an instruction stream.

Ilan: Definitely.

Ian: As long as you are smart about where instructions are located within each other. I think one of your diagrams shows that. Even though I sat through the briefings and tried to work with you guys on some of this explanation, I may actually be finally getting it!

Ilan: One more thing about this is that a CPU core, any instruction set core, even a GPU - goes through the instruction stream and reconstructs the graph, and it does a good job at that. But at any given point in time, it is only executing a few instructions, not your whole program, not your whole inner loop.

Ian: This is when we say an IPC (Instructions Per Cycle) of 2, 2.5, or 3, even if it is a 10-wide core.

Ilan: Exactly. Your inner loop might be a complex formula. If you are in HPC (High-Performance Computing), it might be a scientific formula that has a lot of components and a lot of computation. That is more than just two instructions, five instructions, or even more than ten. When you run this on hardware that runs the graph, you can pipeline through this a lot of threads, a lot of context, and a lot of iterations in your iteration space on different stages at different places in the graph. So that every ALU is actually executing every cycle. So now it is not two IPCs or 10 IPCs; it is the whole loop every cycle.

Ian: And that’s where the element of data flow comes in.

Ilan: Exactly. You can only do that with data flow.

Ian: One thing that comes to mind there is that you made a big argument on the launch of Maverick 2 about how a lot of a core is dedicated to dealing with memory, whether it is translating addresses, looking up addresses, and then all the caches involved in that. But in the diagram, you said with our architecture you don’t need such a big MMU (Memory Management Unit) involved. However, you still need to funnel the bandwidth in. Can you describe how that works?

Ilan: There is a lot of secret sauce there, and we have patented one of the things, which is the reservation station and the dispatcher. It takes data that is coming from the memory or from previous instructions and pipelines it into the data flow graph. Moreover, there is an MMU in our system, but unlike a CPU MMU that has to deal with your whole program, ours is different. A single CPU MMU has to deal with all the memory accesses that you have in your program and it uses a TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer).

In a data flow graph, when you spread your memory accesses around geographically across the chip, every MMU has to deal only with a small set - let’s say 10 or even fewer, like two or four - memory accesses. So a certain memory access instruction in your program has a very different memory access pattern than your whole program. You can optimize that much better than you optimize MMUs in a CPU.

Ian: So that means for the modern codes that we look to run, whether it is anything from HPC - which I know this chip is targeting - or machine learning, we can still get the streaming in. I say “stream” because it is a very common benchmark, but are there any benefits to the bandwidth you can ultimately get out of it?

Ilan: Yes, of course. Think again about the data flow pipeline. Every memory access instruction is part of the pipeline. So you could have a lot of outstanding memory accesses coming from the same element in your code at the same time. They are independent because they are running different threads, so they can be outstanding at the same time. The amount of outstanding memory accesses going to the DRAM or to the cache is much higher than you would find in CPUs and GPUs. It is an order of magnitude higher.

Ian: Do you still get issues like false sharing?

Ilan: Well, it depends on how you do the allocations. Naïve allocations come up with false sharing; you get that. But one of the things about our hardware is that we don’t try to analyze that at compile time and deal with it because that is a very hard problem. Nobody was able to do that. What we do is we collect telemetry, and at runtime, we adapt and change the allocations. So you might have your memory pages or memory blocks allocated at one place, and then during runtime, we figure out that there was false sharing and we move them around. That is why we actually use the MMU because it allows us to keep the virtual addresses and change the physical addresses around.

Ian: When I am thinking about a classic CPU architecture, where you have the prefetch and the decode stage, and a lot of modern architectures have µOp-caches after they have done the decode and rename. Given the nature of the architecture, because you are compiling the graph, that just doesn’t even need to take place?

Ilan: Yes, we don’t have an instruction fetch unit. We don’t have an instruction cache. We don’t need all of that. We don’t have an instruction out-of-order engine or reorder buffer for instructions. We don’t need that.

Ian: As you look at the levers that you can pull for increasing performance in the future, what levers are accessible to you? Because if I look at a modern CPU core, they might say we have a bigger TLB, more prefetch units, better page walkers, more ALUs, more branch units, more load stores and so on.

Ilan: There is so much! But the jargon is so much different than CPUs.

We have certain blocks and they implement parts of your pipeline. Coming up with the correct balance of how many integer units you have, how many memory access ports, the ratios of those compared to memory, how many threads you can have capacity for, and absorbing latency so that the pipelining becomes full throughput. A lot of these things are degrees of freedom that we can play with and customize.

I can tell you that we have done a lot of work analyzing the common kernels in HPC to come up with a mix that is good for everything. You cannot get everything; that is too much to ask for! But we found a good mix that allows us to run a wide range of applications at full throughput at very high performance. The point is beating the competition, and not just by a few percent, but by an order of magnitude.

Ian: As an analogy, if we took a modern CPU core and designed it just for weather prediction for example, you might change the ratios, but it would reduce performance elsewhere.

Ilan: Absolutely. I’ll give you an example. We generate more than one configuration at a time. We generate one configuration, another one, maybe tens of them, maybe hundreds of them, and replace them. The ability to switch from one configuration to another is hardware-accelerated. That is something we have learned over the years.

Specifically for weather simulations, those have hundreds of different kernels. They have hundreds of different physics. There’s the dust, pressure, temperature, things that are going vertically and horizontally - and all kinds of things. It is a challenge generating that amount of different configurations and still switching between them efficiently. Compared to, let’s say, a molecular dynamics one that has only a few where you are going over a loop lots of times. Different challenges in different applications.

Ian: That was one of the questions that came out of the launch - when we look at other data flow architectures, they often define the data flow and it is built into the binary. When it goes to runtime, it just lays it out on the chip, runs that, and cycles through.

You guys said that you can have a configurable data flow while the kernel is running.

That switching penalty that the others have - if you want to call it a penalty or a latency - is low enough on NextSilicon?

Ilan: Yes, exactly. But also note that we are not generating configurations on the fly at microsecond speeds. We generate new configurations every few seconds according to telemetry. When we generate configurations, we generate a set of configurations, and those can be reconfigured on the fly while the application is running at microseconds and even nanoseconds in some cases. So there are two different layers of granularity.

Ian: Your CEO, Elad Raz, is very hyped up that that is one of the key innovations.

Ilan: Yes, it is. As you know, this is Maverick 2. That suggests that there is, or was, Maverick 1! We learned a lot from that. Part of what we learned is that the overheads are very important. So if you have your kernels running for 100 microseconds and your overhead of switching a kernel is 100 milliseconds, that doesn’t work. We have to make it much smaller. That is what we did. We added the required hardware acceleration to get those overheads to the minimum. We have plans to do that even further in the future.

Ian: But I guess if you are being malicious with carefully crafted code, you can make it look like it’s really bad. But the same with any other normal core.

Ilan: You can do that to a CPU as well!

Ian: Yeah, trust me, I’ve done it to CPUs. I’ve done it to GPUs!

Ian: Talk me through going after HPC. Because right now we are in this sort of AI craze with machine learning. I work and cover so many companies in that space where all they are doing is either a mixture of CNN, DNN, or Transformer models. It is interesting to hear your opinion of why HPC was the goal with Maverick 2.

Ilan: Don’t get me wrong! we are not neglecting AI. Of you look at it from the financial point of view, HPC is a very small niche market and the AI market is like three or four orders of magnitude larger. There are trillions over there and there are only a few billion in HPC. We strategically chose to go after HPC for multiple reasons.

One of them is that it is large enough to get the technology to a maturity level. It has the most sophisticated customers and players that can play along and absorb all this. They’re not just willing to learn, they are willing to take the time and effort to optimize, to deal with bugs that happen, and to deal with the wrong architecture and give you feedback that is useful for the next generations of the chip. So they are helpful in that sense. They are almost not customers but partners in the development, and you don’t find any of that in the AI market.

Ian: My criticism for the HPC market, and given we are at Supercomputing, we all love the HPC market, is that sometimes they can be very slow to put in orders. Sometimes systems end up being used by students who are on three, five, or seven-year programs and don’t stick around.

Ilan: That is why in the HPC market we went to the largest and biggest computing centers. As you probably know, we work with Sandia National Laboratories. These guys are the largest national laboratory in the United States. They have seen every possible platform that was ever manufactured and they can give us feedback that is practical. Like: “Applications are doing this,” “Applications are doing that,” “This is what users care for,” “This is the usability that people expect,” “This is the performance that if you don’t have, you’ll get thrown out.”

Some of the things we’re seeing.

First of all, the STREAM benchmark. That’s a very simple thing; it just shows that we are able to utilize the HBM bandwidth.

Then you go to things like GUPS (Giga Updates Per Second), which is a random memory access. This shows you what happens when your cache is completely useless because GUPS is always cache missing. It doesn’t vectorize, it doesn’t coalesce memory, it doesn’t do anything like that. Even in GUPS, we are able to utilize the HBM to the fullest. The numbers we get are unheard of on any other platform on GUPS.

Now GUPS is just one synthetic specific microbenchmark, right? It is synthetic, but a lot of the applications on the defense front, and even in HPC, behave similarly. They have something that is not very regular; the memory accesses are just going around, sparse workloads or something like that. This is an immense benefit that we have that other platforms don’t.

Ian: So do you expect to be compute-bound in most cases?

Ilan: Actually the opposite. I think the compute is so performant that we are taking workloads that are typically compute-bound and making them memory-bound, going right up to the roofline. A lot of the platforms have a certain roofline, and you can see the peak and the memory bandwidth, but they can’t reach the top. Our system and our architecture is able to maximize that and get to the top.

Ian: Are you getting any feedback on that front that’s making them reconsider how their internal code is structured to change that model, to change where they fit on the roofline?

Ilan: Regarding code changes - it is our stated goal to require zero code changes.

But once you do that and you get your portfolio up and running with acceleration, you get the appetite. You have your few champion applications that you want to invest in. There are plenty of things you could do to your code to make it run faster. One of the things that we provide is the tools to identify what is blocking your performance and what is slowing down your application, and recommend changes that you could do to your source code. It just so happens that these changes are often very good for other platforms as well. So if you just refactor your code in this way, you get even better CPU performance.

Ian: People might be familiar Intel VTune and similar software - you’re talking about something along those lines?

Ilan: It’s a profiler tool. You could say it is very different than VTune because the architecture is different, but if you are talking about the user flow, then it is something similar.

Ian: Going back to that optimization on Maverick 2, I understand that by profiling the code, by instrumenting it, the hardware will then dedicate more resources to the parallel parts versus the serial parts. I’ve seen some conversations in the market asking if they right write really bad code, it will work well. Or similarly, if the code is going to be adjusted, how can I optimize for the underlying architecture? Because it is such a different way of thinking against programming for CPUs and GPUs.

Ilan: We don’t do automatic parallelism. We’re not inventing parallelism out of nowhere. You still need to be smart and you still need to express the parallelism in your program. Not necessarily vectors. It could be anything - using Kokkos, CUDA, whatever. You need to express the parallelism in your program. You cannot write bad code and expect it to perform. It will work, but it will not perform.

So you can’t write serial code and expect it to be vectorized. It doesn’t work.

But once you write your code in a parallel fashion, then we can scale up the parallelism and concurrency in the chip.

Ian: So do you have to write it in the SIMD model of GPUs in that way?

Ilan: You could write SIMD code, but also you could write OpenMP code - you could write Kokkos code, you could write CUDA code. Anything that expresses parallelism at the source code level compiles into intermediate representation and we understand what the parallelism is. We take that from there.

Ian: You also advertise a ‘bring your own code’ model. So does it mean it supports CUDA? Does it support the other GPU languages? And given where Nvidia sits on other people using CUDA code, have you had any issues on that front dealing with it?

Ilan: Not yet. We will see how that happens. I think the “CUDA moat” is a problem, but we will see how we can alleviate that. One of the possibilities is to use HIP. Other vendors have gone that way and a lot of codes are being rewritten from CUDA to HIP to bypass the moat. We still have a few tricks up our sleeve! There are legal issues there as well, so I won’t go into that in this interview, but we believe that we can do that.

Ian: Turning to machine learning, I know you guys are planning a future chip that’s more focused on machine learning. How are you viewing that market for your architecture? Because it’s one thing to go after HPC that has to deal with everything and the hardest codes in the world, to something that might be insanely regular or a lot more predictable. Because we were talking about how you change those degrees of freedom to optimize. Can you be a Transformer-specific or CNN-specific design?

Ilan: One thing to say is that the data flow architecture is more efficient. You can take that it is more efficient than a CPU or GPU, even if it’s a CPU or GPU that’s designed for AI. However, if somebody wants to make a chip that’s LLM-specific, inference-specific - even go specific into that, do only FP4, do away with the FP64 - that is going to be more efficient than our chip no matter what you do, because you invest all the silicon in just one specific use case.

If we had more resources and time, we would go about that and make a chip that could be more efficient than the other competitors using data flow, solving a specific problem for a huge chunk of the market. But that would not take us in the direction that we want. So we’re avoiding going there and spending the resources there. Instead, we did a chip that is an HPC chip. We are looking into how we can do AI with that and how we can do a product that’s viable for AI with that.

Ian: But is the intent to still at least maintain FP64 performance?

Ilan: Yes, we are an HPC-first company. There is a lot of interest now in workloads that are HPC+AI. For example, people are training their AI using an HPC simulation.

Ian: I’ve often found that at this event, that’s a very difficult conversation to have with some people who are unwilling to accept that is the way it’s happening.

Ilan: It’s happening! And if you’re looking for a system to run this kind of workload on, then you have to run both a GPU or an AI accelerator as well as your HPC accelerator. The newer generations of GPUs are not good for that. And our chip has a very good potential in that market.

Ian: One trend in this industry is that chip packages are getting bigger. The advent of chiplets means more silicon and ultimately more compute, more power. I noticed that Maverick 2 has that chiplet infrastructure. Is there anything unique in that chip-to-chip boundary or stuff that has to be considered at runtime?

Ilan: Oh yeah. So let’s go to basic principles. You’re saying this as a fact, chips are getting bigger. But did you ask yourself why? Why do people want bigger chips? It’s faster to keep it on silicon sure, but it is more than that. It is faster to have the dies connected together because you have lower latency and higher bandwidth.

But when you scale out, when you make a system, when you design your application and your system in a way that is scaling out, then probably that’s not the main factor. What people want is density. They want to put more silicon in the same rack compared to just taking more real estate, and that eventually comes up into power and OpEx and other factors.

We’re not strangers to that. Our chips are, as you said, going into that. We’re looking in future generations to improve the connectivity further so that neighboring chips can talk to each other and you can scale workloads, and even things like AI when you shard your huge model to do that across chips. Even today you can do that with a Mellanox NIC and RDMA, but you want something more integrated. That’s the way of the future.

Ian: In HPC, MPI is often preferred. Are you doing anything specific for MPI when it comes to multi-chiplet?

Ilan: So in the Sandia system, the Spectra, we have just Infiniband RDMA doing MPI kind of like GPUDirect, when the accelerator is driving the NIC without involvement of the CPU. But we have more tricks up our sleeve.

Ian: Wait, more tricks in that silicon or to come?

Ilan: Both!